City-led infrastructure is a powerful tool for reducing carbon. From the roads we build to the cars we drive, the emissions we produce from day-to-day travel can, and should be, reduced in order to mitigate the effects of climate change.

Cities around the world are realising the impact of air pollution as a result of emissions, damaging the planet, as well as the health of the general public. London, for example, has implemented policies to reduce air pollution by having low emission zones in order to reduce densely polluted areas in and around the city of London. By applying these measures, individuals are directed and guided in their day-to-day decisions to consciously think about their individual emissions, as well as the damage high polluting modes of transport such as older generation cars have to the public and beyond.

Read next: Volkswagen ID.3 review: The best electric hatchback?

Travel and transportation are huge elements of everyday life. For work or pleasure, the way our technological advancements have allowed us to travel without thought has been a luxury for many. However, the consequences of such high emitting, regular travel are seemingly becoming clearer and clearer. In the UK alone, there were 32 million cars registered driving on the roads in 2021, each providing its own individual footprint and subsequent damaging emissions to the planet. Considering the sheer amount of cars on the road in the UK alone, it is no wonder that the implementation of clean air zones in major UK cities are being implemented as city policy.

Read next: Audi A3 TFSI e review: A sporty plug-in hybrid

The announcement by the UK government in late 2021 to ban the sale of new petrol and diesel cars by 2030 is inviting but still falls short of the necessary infrastructural and technological targets needed in order for the UK to further transition away from its fossil fuel addicted ways. The need for clean public transport with viable routes accessible to all is a solution, bringing low-carbon technologies to the forefront of the transition. Overhauling current transport systems to replace them with cleaner and greener vehicles gives rise to a necessary transition. Fewer cars on the road and greater uptake of individuals utilizing green transport would have huge benefits not just in the UK but all over the world.

However, a proposed and potential investment of £27 billion towards the creation of new roads within the UK could spell danger for further investment into public transportation, with the UK government looking to increase its development of road infrastructure in order to accommodate for growing numbers of travellers and the potential for traffic generation as a result of its increase. Inviting the creation of new roads and transport links dedicated to public transportation would be welcomed and encouraged, seemingly because it would further create options and support for public transport while deterring drivers of petrol and diesel cars from continuing to use their vehicles on the roads. However, the UK’s discourse to push for electric individually-owned cars over investment in green public transport is troublesome, though the ban on petrol and diesel vehicles will surely encourage individuals to uptake public transportation, meaning subsequent investment is needed.

Read next: Equipmake is creating the world’s most power-dense electric motor

A proportion of the £27 billion investment towards new roads would benefit public transport hugely. There is a need to make public transport systems more reliable so that they can serve communities who already depend on them and be a viable option for many more. By taking a broad and long-term view, investment in public transport can have a positive impact on both society and global warming. This means investing in resilient infrastructure now so that unexpected costs and disruptions from changing weather conditions do not cause further damage in the future.

A large proportion of the investments can first be invested into fleets of cleaner vehicles, creating a system accelerating towards carbon zero through electric busses and trams. As an example, England hosts 35,000 buses across its entire fleet and only 700 of these are currently electric, that’s only 2% of the bus fleet. A brand-new electric bus costs £550,000 (California Fuel Cell Partnership, 2016) and so the cost of replacing all of the current internal combustion engine buses with electric buses would be £18.9 billion. A hugely significant amount of money, but still only 70% of the investment promised for new roads.

Buy a car phone mount on Amazon (Affiliate)

However, a much more economically, and environmentally friendly method of electrifying England’s current fleet would be to repower existing diesel vehicles with all-electric components, at a cost of £370,000 per bus (Pan, 2022). Overall, this would cost £12.7 billion, less than half of the £27 billion investment towards new roads. The government are a long way off electrifying the whole bus fleet, but they are making progress as a £3 billion National Bus Strategy pledged 4,000 new British-built electric buses. Local authorities can bid for up to £120 million of funding to purchase zero-emission buses using the zero-emission-buses regional (ZEBRA) scheme.

Read next: Electric buses spark new safety requirements

Then, further investments can focus on positively impacting the economy by creating jobs and generating returns. A report (C40 & The International Transport Workers’ Federation, 2021) has calculated the return-on-investment public transport potentially could provide as for every £1 invested, it could generate £5 in economic return. Additionally, the report inferred that 1.8 million jobs could be created from a £27 billion investment into public transport. This can all be created by making public transport more attractive to the population. For example, by adding extra routes, earlier and later times, increasing frequency and coordinating different modes of transport. Modelling has shown that a rural bus network to every village, every hour would require £2.7 billion a year, which is just 10% of the new roads budget (Christopher Hinchliff & Ian Taylor, 2021). Additionally, shade corridors have been seen in Pheonix, USA, and could also be implemented in the UK as dry corridors to allow passengers to get to and wait for buses more comfortably without getting wet.

Truly accessible, frequent and reliable public transport would provide an option for people currently reliant on cars for essential journeys and may serve them better than electric cars, without increasing the need for a complex charging infrastructure. Ideally, a charging infrastructure would use renewable power if it is not to simply shift the emissions from point of use to a power plant.

Read next: Should you buy a used electric car?

While free public transport is not necessarily the best way of enticing motorists out of their cars and reliable, frequent transport is a more important consideration, many cities in Europe have introduced free transportation programs. Since 2013, local residents in Tallinn, Estonia have been able to ride the city’s public transit at no cost and this has resulted in a 3% reduction in car use. While 3% may not sound a lot, there are over 200,000 cars in Tallinn amounting to a surprising 8,000,000 kg CO2e.

Luxembourg is considered to be the first to extend this offering nationwide; since March 1st 2020 Luxembourg became the first country in the world to make all public transport in the country (buses, trams, and trains) free to use and Germany is currently considering making their public transit system fare-free. Today, at least 98 cities and towns in Europe, the USA and around the world have some form of free public transport. In some areas, only residents can use it, or certain groups, such as senior citizens.

Read next: Our favourite dash cams to mount inside your vehicle

In the UK, senior citizens can obtain a free bus pass, which forms the underlying premise of the recent Timothy Spall film ‘The last Bus’ where Tom, a recently widowed man who decides to travel the length of the UK with his wife’s ashes, using his free bus pass for the entire pilgrimage.

Rail and trams should also be considered in the mix. In 1992, Manchester reintroduced Trams after an absence of almost 50 years. With passenger numbers swelling to over 40 million journeys a year. Sheffield followed shortly after in 1994 then Croydon, Nottingham and Edinburgh followed suit with their own electrically powered tram systems. All of these offer much lower carbon solutions to the need for transport than private cars of any kind.

Read next: The Decarbonisation Plan: What does it mean for fleets?

While these examples are all in city settings and what is needed is a public transport system that meets the needs of rural areas too, the uptake by passengers supports the case for public transport provision. The £27 billion, currently earmarked for new roads, could certainly make a difference both to greenhouse gas emissions and to quality of life.

Considering a more nationwide approach for upgrading the public transport system, there is an option to invest in the railway network to achieve a more environmentally sustainable operation of the system. The electrified track coverage of the Great Britain railway system is currently 37.9% of a total route length of 15,935 km (Office of Rail and Road, 2021). That means 62.1% of the total route length is currently diesel-based, approximating 19,407 km of non-electric track length. It is also worth noting the difference between route and track lengths here to avoid confusion. In 2020-2021, an effort was made to further electrify the system such that 179 km electric track length and three new mainline stations were added to the railway network. Assuming that the cost of delivering a single-track kilometre in Britain is approximately £1m (Barrow, 2019), it would cost £19.4b to transform the remaining, non-electric 19,407 km of the railway system. Furthermore, research has shown that a range of project management options are available to make the electrification process efficient and this would reduce the final cost by 30-40%.

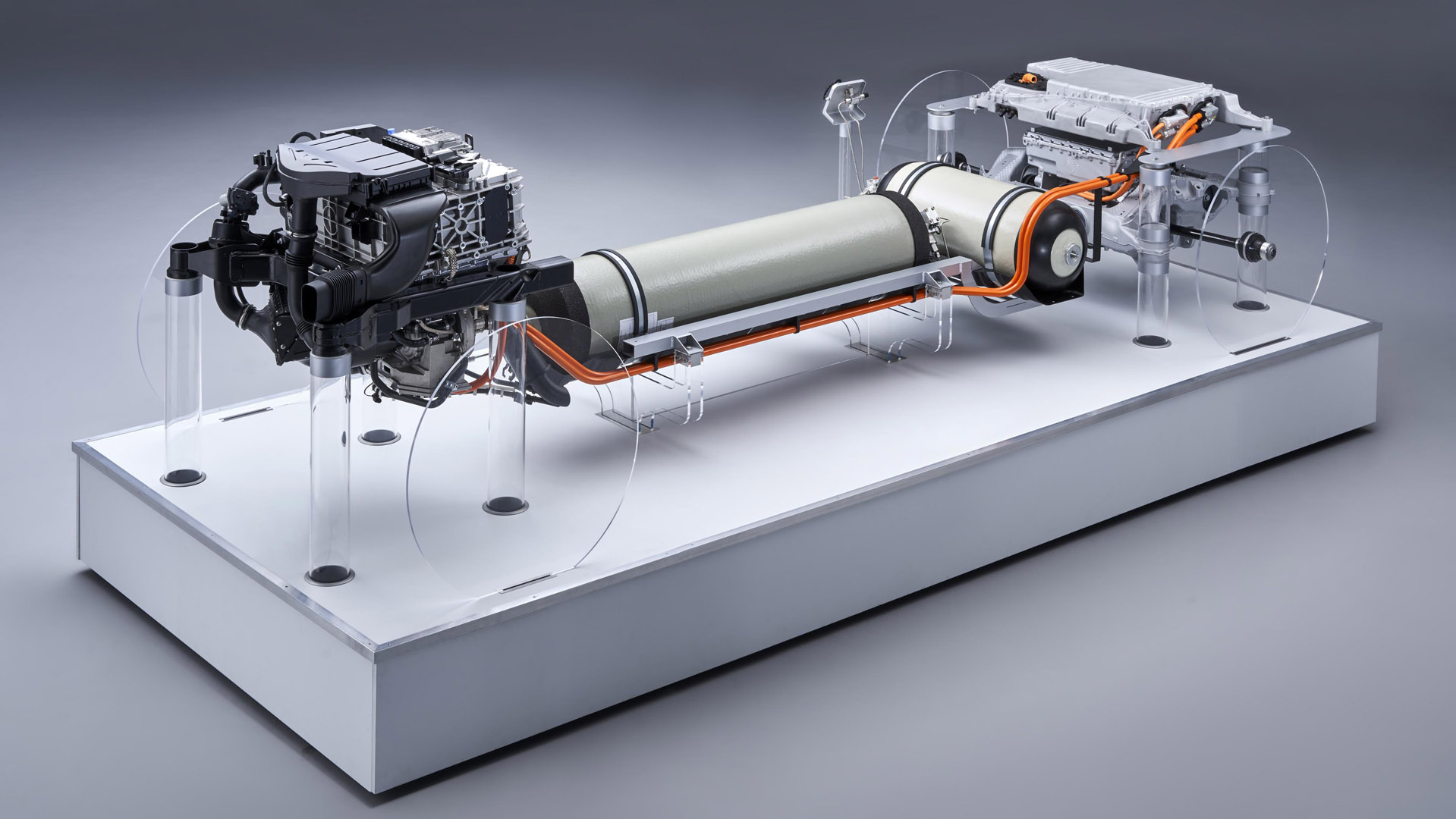

Read next: Can hydrogen-fuelled transport be mainstream?

In 2020-2021, there was 354 and 154 million litres of diesel consumed for passenger and freight trains, respectively. This, in turn, resulted in approximately 977 and 422 KTonnes CO2e emissions (Office and Rail and Road, 2021). The majority of freight trains are still diesel-operated and this continues to negatively impact the environment. By transitioning to the use of electric trains, the emissions could be reduced by 50% per passenger per kilometre (BBC, 2019). Alongside electric trains, solar and hydrogen trains can help reduce the UK’s emissions (Logan et al., 2021), enabling the country to meet its target for the Paris Agreement. Projected data for 2050, assuming 100% hydrogen train operation in the UK, suggests an 85% reduction in total emissions in comparison to the operation of 100% diesel train. This area of advancement and efficiency in technology for solar and hydrogen trains warrants further explorations from scientists and transport planners but is still very promising.

Given the population and economic growth in the UK, and the subsequent need to expand the road system, to meet a projected number of 350 billion vehicle miles by 2040 (Department of Transport, 2017), the £27 billion investment in roads seems to be a very direct solution. Building extra roads to meet 350 billion vehicle miles simply encourages the wrong behaviours, if we are also to achieve net-zero carbon by 2050. However, encouraging people to use alternative means of transport, and spreading the cost of the proposal to upgrade multiple sectors of the public transport systems are believably a much better option in the long run.

Read next: Our favourite inexpensive car phone holders

TotallyEV would like to thank Dr Torill Bigg, Chief Carbon Reduction Engineer; Joshua Farnsworth, Carbon Reduction Engineer; Aaron Yeardley, Carbon Reduction Engineer; and Luan Ho, Carbon Reduction Engineer from Tunley Environmental for their contributions to this article.