When the UK government announced in November 2020 that it would ban the sale of new petrol and diesel vehicles by 2030 – ten years earlier than planned – it was just the shock we needed to propel an EV revolution. But while politicians can nudge us towards EV adoption, it takes more than top-down government policy to manage the transition.

The automotive industry is responding to this challenge with admirable speed. Electric vehicles might not have the range of ICE cars yet, but they are catching up quickly, and while they are more expensive at present, the price is falling fast and should reach parity by the time the government’s deadline rolls around.

Read next: Do electric vehicles hold their value?

Meanwhile, significant new developments in battery technology are on the horizon. In early January 2021, an Israeli company announced an EV battery that can be fully charged in just five minutes, offering us the tantalising prospect of “filling the tank” in almost the same time it takes to fuel petrol and diesel vehicles. Progress? Absolutely. But perfection? Not yet.

To get a view of how companies are helping to power the transition to zero-carbon transport, TotallyEV reached out to David Watson, CEO and founder of Ohme, a UK technology company that focuses on intelligently finding the best charging times and prices – ultimately making the leap to an all-electric even more appealing for aspiring drivers due to potential cost-savings.

Buy a car phone mount on Amazon (Affiliate)

Bumps in the road

The prospect of longer-ranged and more affordable vehicles, of five-minute fill-ups and nationwide charging infrastructure, paints a rosy picture for the future of EVs but a promise is not enough. Cost is still the dominant consideration of any purchasing decision, especially during such uncertain economic times.

It’s not just about bringing down the price of the vehicles, however, as it’s just as important, to give motorists maximum control over the cost of charging their vehicle. This is especially important given recent stories about electric forecourts, which can cost nine times as much as charging at home.

Just as critical, is the need to address significant questions over grid infrastructure and whether the UK can possibly support the expected 10 million new electric vehicles on our roads by the end of the decade. If these all plugged in at the same time – say, at the end of the day, after the daily commute – it would require us to almost double our peak electric generation capacity, and add an overall increase of 12% to the total electricity generated today. That’s equivalent to building another 20 large gas-fired power stations simply to sit in reserve and only provide power at peak times.

The road to zero-carbon mobility, is not without its challenges. Challenges which individual initiatives – better batteries, cheaper vehicles and extended infrastructure – are helping solve.

Read next: Renault Zoe review: Best electric family car?

The smart way to sustainability

Die-hard petrolheads, climate change deniers and renewable energy sceptics love to point out that with sustainable electricity generation, the wind doesn’t always blow, nor does the sun always shine.

But this gotcha is not quite so clever as it seems to the sceptics. Renewables aren’t an EV killer; in fact, the opposite is true. Because energy is cheaper when it’s most abundant, variable electricity tariffs dramatically lower the cost of charging EVs during times of low demand. Electric vehicles can therefore act as a giant distributed battery, soaking up energy when it’s cheap and plentiful.

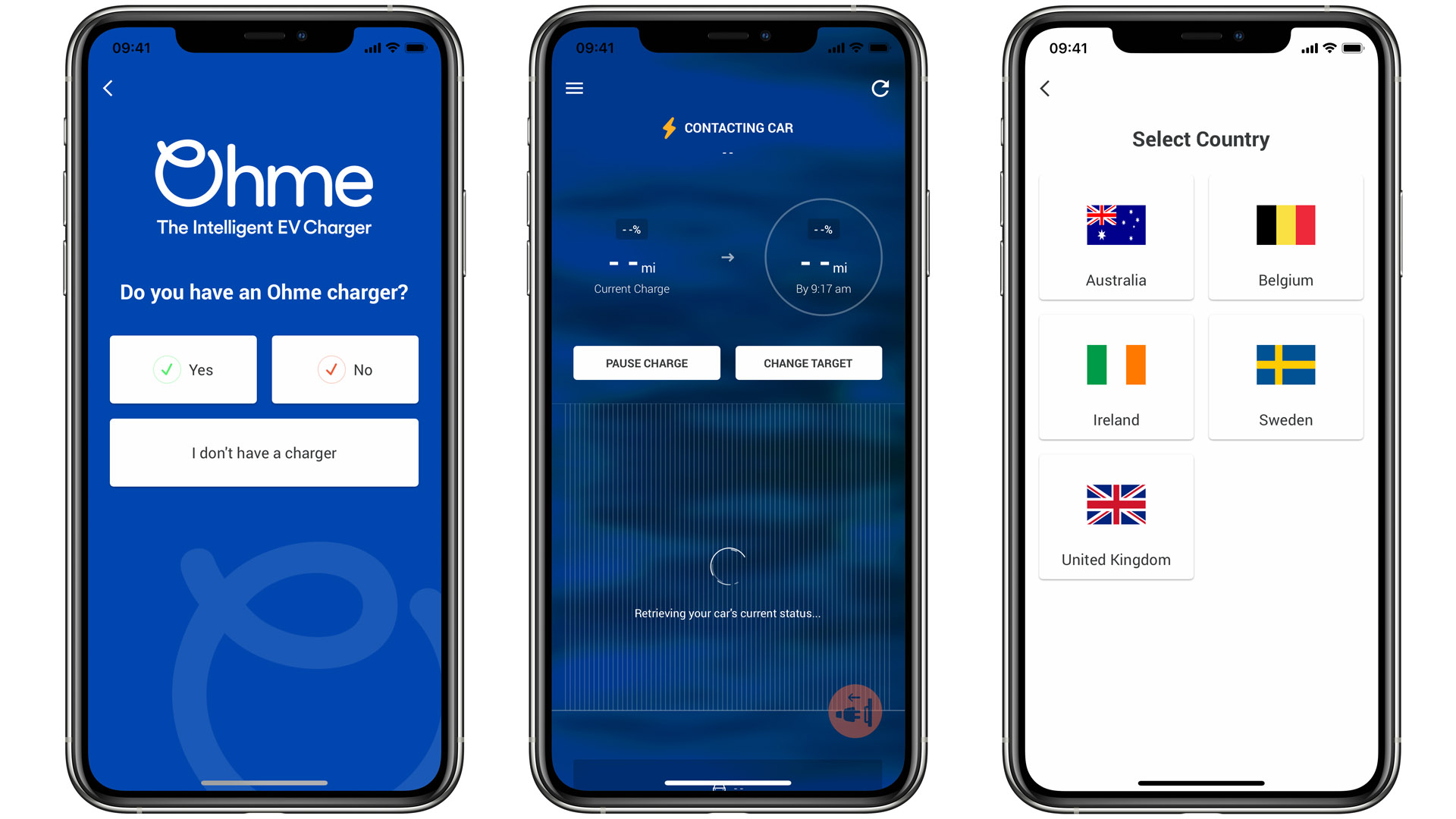

The technology required to make this happen already exists, in the form of smart chargers that Ohme and other leading green tech companies make, which enable users to decide the price they want to pay to charge their EV. By plugging in overnight and setting a limit on how much they want to pay, drivers can benefit from variable energy tariffs to charge their cars far more cheaply than with traditional chargers. It’s not uncommon for some people to earn money by charging when tariffs fall below zero, although, probably not enough for anyone to consider giving up the day job just yet.

Read next: Mini Electric review: Style over substance?

Much as we need governments to give us a shove in the right direction, change cannot come solely from the top down. The ban on new ICE vehicles must be complemented with a bottom-up revolution that gives drivers a reason to go electric, while also solving the looming grid capacity challenge.

So how can we solve the cost problem? If mass EV transition is to be made a reality, the journey to an electric future must be made as accessible as possible. This means ensuring all EV owners can make use of smart charging systems that can significantly lower the costs of running their vehicle.

The good news is that the barriers are already being lowered and companies are rolling out free intelligent charging technology to EV users. Apps, like the one from Ohme, bring the benefits of smart charging to the owners of electric vehicle chargers. Drivers using this technology can set charging preferences, create charging schedules for their daily commute or weekend trips, control their charging remotely, and view a range of metrics including the cost and CO2 savings compared to standard charging, all for free.

Read next: Audi e-tron review: Best premium all-electric SUV?

And it’s not just motorists that benefit from smart apps like these. The insight into charging behaviours – when they charge, how much power they draw and for how long – is crucial for energy companies and infrastructure operators so that they can manage generation and grid capacity more intelligently.

The future, not just of motoring, but of our energy strategy, is well within our grasp. If we can make smart charging the standard, whether through an app, cable or other technology, and encourage more people to choose time-of-use tariffs, drivers can save around £300 a year per vehicle every year. That’s exactly the sort of nudge that can convince motorists to take the plunge and make their next car electric.